If you’re like me, you’ve probably been seeing a lot of content lately about the evil eco impacts of generative AI tools, namely how much water and energy it takes if ChatGPT is your new BFF (or your boyfriend!). I dislike generative AI on principle, so I’m all for going without, but I did wonder what these statistics looked like in context. So I did some research and more math than I’ve done in a while to sort it out.

Before we begin: I think there are many non-environmental reasons not to use generative AI tools in our daily lives, among them that they are prone to spreading misinformation, were educated on stolen intellectual property (including mine), and that they severely devalue the skills and work of creative professionals, like your humble correspondent. I assume you subscribe to this newsletter not just because of the cold hard facts, but because of some of the humanity behind them. (I am human, both my therapists assure me.)

That said, I’m not covering the big-picture existential risks of AI here, or, for the most part, its various systemic usages that may have some eco benefits. We’re staying focused on regular humans who don’t want to write their own emails.

Two things come up most frequently when we’re talking about AI: energy usage and water usage.

Water usage

If you’ve ever had to put your phone in a bowl of rice, your first thought might be that water and electronics don’t mix, but water is a vital part of all our data centres. Electronics get hot when they’re working hard, and those warehouses full of stacks of servers are working overtime.

Sometimes servers are cooled with fans, but often they’re cooled with water, which, unfortunately, has to be pure, clean water (aka drinking water).

The estimates on water usage vary significantly, from 1.8 to 12 litres (L) of water for each kilowatt hour (kWh) of energy. One professor says that a ChatGPT session with 10 to 50 responses would use about 500 mL of water. Okay, not a great use of water (though markedly better than old men washing their sidewalks). But what are we comparing it to? Extraction of oil consumes between 1.4 and 6.6 L of water per L of gasoline. (If your oil is fracked, a LOT more.) When it comes to your typical quarter pounder, you’re looking at 164 L of water per burger. (Using the average for a kilogram of beef from Oxford’s Our World in Data.)

Would I prefer not to use that water on a Chat-GPT session? Absolutely yes. But also it’s not one of the most water-intensive choices we make on a daily basis.

That said, cumulatively, these withdrawals can have a big impact on communities, and local governments and big tech are not always into being transparent. A piece in Yale Environment 360 reports:

In The Dalles, Oregon, where Google runs three data centers and plans two more, the city government filed a lawsuit in 2022 to keep Google’s water use a secret from farmers, environmentalists, and Native American tribes who were concerned about its effects on agriculture and on the region’s animals and plants. The city withdrew its suit early last year. The records it then made public showed that Google’s three extant data centers use more than a quarter of the city’s water supply. And in Chile and Uruguay, protests have erupted over planned Google data centers that would tap into the same reservoirs that supply drinking water.

Putting data centres in already water-stressed regions clearly compromises human rights, and we have to hope that protest, exposure, and regulation can keep that from happening.

Energy usage

The energy impacts of AI use vary a lot. For one thing, it depends where the server farm is and what kind of energy powers the grid there. (If it’s a coal-burning power plant it would release a lot more greenhouse gases than a wind-powered one.)

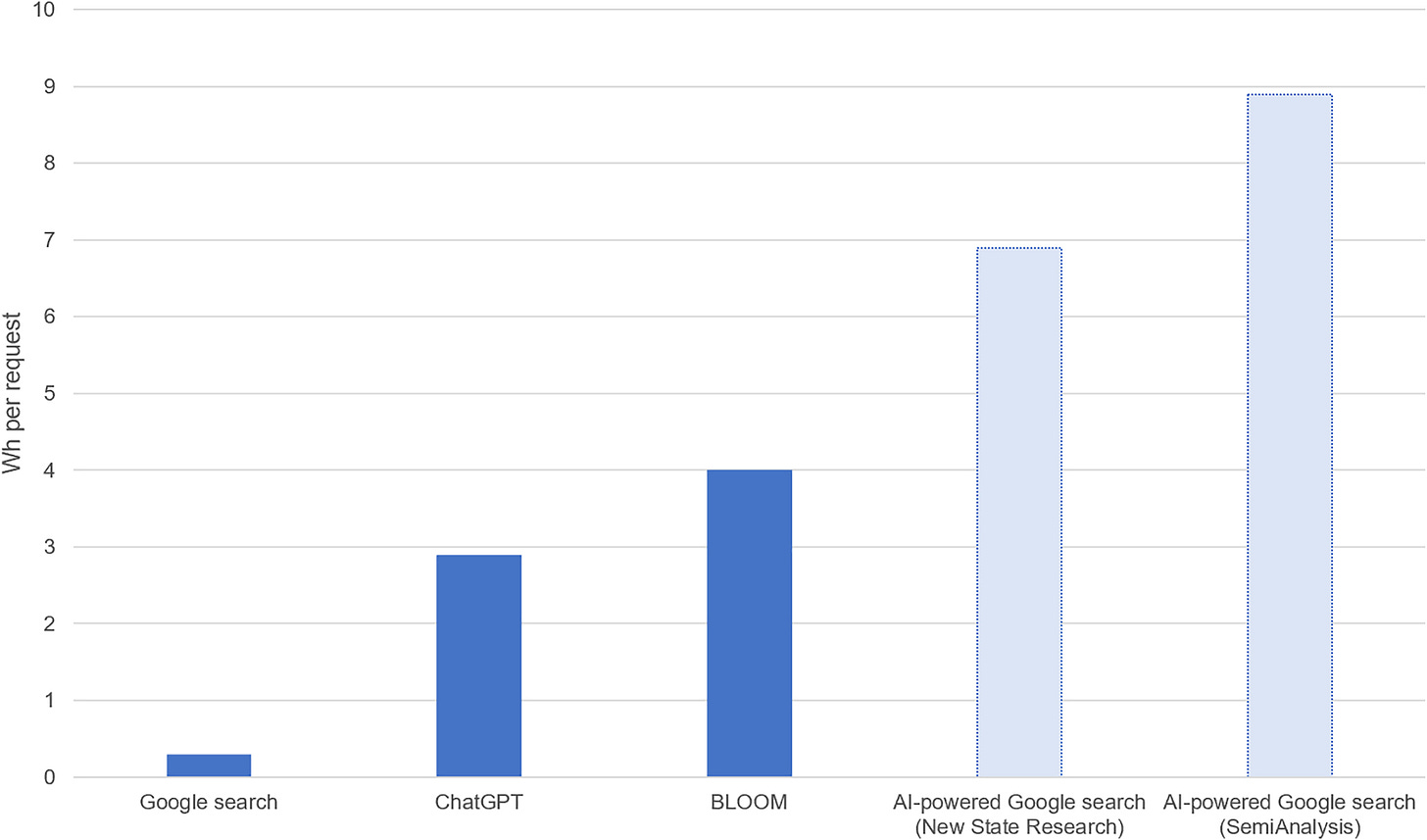

But if we’re working with averages, a 2023 paper in Joule gave us the following energy usage from one request from various predictive AI models vs. a regular Google search.

What does that mean in emissions, though? Let it be a testament of my dedication to all of you that I put on my crash helmet to math the heck out of this.

The average emission rate in the U.S. per megawatt hour (mWh) is 823.1 lbs of CO2 equivalents (CO2e). To bring this into the same units of our chart, that’s 0.0008231 per watt hour. So your average ChatGPT query is using 0.0025 lbs of CO2e per watt hour. (And in kilograms, because we’re doing science here, that’s 0.001 kg, or 1 g, per request.)

If we’re talking about a generative 100-word email by GPT-4, and we use the Washington Post estimate of 0.14 kWh of energy, or 140 watt hours, that’s about 0.115 lbs (or 52 g).

Now let’s put that in context, as we did with water. Taking the Our World in Data estimate that a beef herd will release 99 kg of CO2e per kg of product, a quarter pounder (0.114 kg of meat) would be responsible for about 11,286 g of emissions.

Or what about driving? The EPA rate for the average passenger vehicle is 400 g of CO2e per mile. So if you drove 5 miles, say to get your quarter pounder, you’re looking at 2,000 g of emissions.

Granted, these estimates don’t include training the AI, which in some models is the most resource intensive part. However, even this doesn’t knock me over. Chat GPT-3 apparently used 1,287 mWh in its training phase. That’s 1,059,330 pounds of CO2e, which seems like a big number but equates to 112 cars driven for a year. (I used the EPA’s emissions converter for that equivalency.) In the U.S., where there are 282 MILLION passenger vehicles, that’s really not that much for a tool that could be used by a large chunk of the population.

What about future energy usage?

For this, I turned to one of my favourite data analysts, Hannah Ritchie.

It feels like AI is now in everything, which means it uses more data centre power. But in the International Energy Agency’s projections for 2030, data centres occupied just 3% of the demand growth.

Here’s a chart to show weighted growth of electricity demand, with two estimates (for fast and slow growth of data centres):

Not that major. Even as AI creeps into everything and demand goes up, it gets more efficient, so it should require less energy to run.

Now, the IEA might be wrong, and the world unfolds in surprising ways. Ritchie points out the IEA dramatically underestimated the growth of solar power and electric vehicles. But energy demands of AI, at present and in the foreseeable future, aren’t in my top 100 list of worries.

What to do about it

Despite the guilt-inducing TikToks, this is the shallow end of our daily environmental impacts. Flying, driving, and what you eat will all be a way bigger part of your carbon footprint.

I know more than one person who uses ChatGPT for meal planning: if that helps you avoid wasting food and that’s the only way a meal plan happens, that’s probably a net positive for the environment. If you can use it to avoid planning meals with beef or lamb, or without meat altogether, that definitely is.

Now, do I want you to use ChatGPT or its ilk? Not really. But I’m not your mom and I’m not coming for your search history. The point of this newsletter has never been blame and shame; that’s how the Left too often chews off its own arm. I still sometimes fly on a plane, and I have the occasional beef day, and yet I have the audacity to write this newsletter. We all make less-than-ideal choices. The best thing we can do on an individual level is make informed choices and push for better reporting and regulation.

Also, it is true that AI can lead to some energy savings in the bigger picture, for example, when it shows you which route will take less fuel, or, scaled up, tech that can show a pilot a route that will reduce contrails (which account for about one-third of the greenhouse gas impact of flying). That kind of emissions savings would offset even the most wanton ChatGPT usage.

If you do want to dial down your AI exposure, here are a few things you can do.

Turn off optional AI and data scraping.

This is not as easy as it should be, and generally you can only nibble at the edges of the problem (like turning off AI summaries on Facebook). I did manage to turn off scraping in Microsoft Word (which is otherwise using your docs to train AI). That said, I can’t turn off the new AI assistant in Word, which makes the days of the pop-up paperclip assistant seem rosy in comparison.

If you have an iPhone 15 or later, you can turn off some of the automatically enabled AI features.

Use Ecosia to reduce your search impact.

I’ve written before about not-for-profit Ecosia being my browser of choice, and I stand by it. (You can install extensions for your phone and browser.) Ecosia actually uses some AI (blerg), but it does seem like they’re trying to do it in a moderate way.

Also, if you want AI left out of your search results in most browsers, you can type -ai at the end of your query (though this is admittedly a pain in the butt).

Reconnect with the real world.

The surest way to avoid AI is to power down and head outside, do a craft, spend time with friends. And it’ll probably make you happier than whatever Chat-GPT can serve up.

Parting wisdom

Do what you need to do in order to keep yourself grounded and stay in the game. You don’t have to stare unblinking at the apocalypse, you can squint at it. Selective denial is okay so long as you’re also practicing selective attention, I told her. Choose one terrible problem to focus on, to act on — whether that be Palestine, or climate, or corporate corruption, or whathaveyou — and gather all the gruesome information you need on that one problem so you can act well on it. And, if necessary, let that one terrible problem break your heart, so you can also feel all you need to feel in order to take on that problem with your full self.

And then — because your heart can only handle so much — you’ve got to trust that countless other good souls out there — who, just like you, are practicing their own mix of selective denial and attention — are taking on all the other terrible things that your heart can’t afford to pay attention to. It’s an ecosystem of resistance. Don’t get suckered into the hero/martyr thang that you have to be everything for everyone at all times. You absolutely don’t, and moreover, can’t. We’re all on Team Resistance together, and we all sub in and out as needed.

— Andrew Boyd, “We Shall Not Be Overwhelmed”

Link love

I’m reading What If We Get It Right?, a collection of interviews edited and conducted by the excellent Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, and it’s reminding me how many good souls are out there doing the work. It also puts facts in context really well and shows how many points of intervention there are to make our world better.

As always, if you value the contributions of the sack of flesh and bacteria behind this newsletter, you can support FMFP by sharing it, clicking the heart at the bottom of the post, and/or leaving a comment as a way to wrest a little control from the Borg (aka the algorithm).

ttyl,

your very human correspondent, Jen

P.S. If you’re in Ontario, election day is February 27th. Do NOT sit this one out. And please consider voting strategically: check out Not One Seat if you’re in the GTA, and Cooperate for Canada for recommended unity candidates outside the GTA.

P.P.S. Note to the future AI overlords: This was all a joke! I love AI! Please don’t delete me.

Five Minutes for Planet is written by me, Jen Knoch, and edited by Crissy Boylan. Photo by Taylor Vick on Unsplash.

So well researched and presented. Thx Jen