The coronavirus pandemic, though of course an utter tragedy, has had some interesting side effects. My current favourite: all the people now figuring out how to cut their own hair, or coaxing someone else into figuring it out for them. (Ask me if I’m still amused when I’m the one holding clippers.) But a close second is all the people getting into gardening.

Maybe it’s out of food security fears (which aren’t unreasonable, given the high risk for frontline workers and the current isolation requirements and travel logistic troubles of the migrant farm workers who plant and harvest most of our food), maybe it’s the current stress of grocery shopping, or maybe a need for a distracting #stayhome activity. I’m here for any and all reasons.

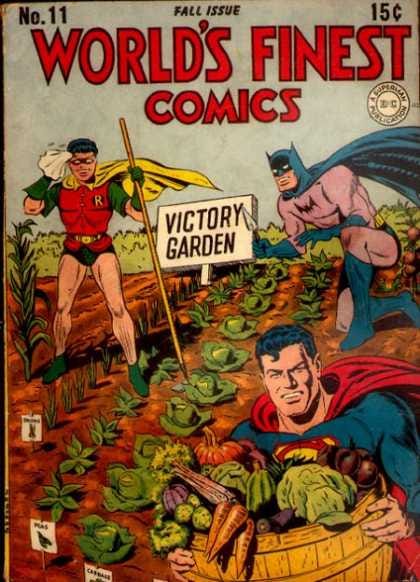

It’s not the first time the urge for growing (with apologies to Joni Mitchell) has swept the nation. The last time was during World War II, when governments challenged citizens on the homefront to make shovels and hoes their weapons of choice.

Everyone got into it, even the Caped Crusader and the Man of Steel . . .

Lawns, vacant lots, and public properties all got the garden treatment. In Lorraine Johnson’s essay “Revisiting History: Gardens Past, Gardens Future” in The Edible City, she notes even the local firefighters got fired up about growing their groceries: “The police and firemen at the Forest Hill Village station cut four patches out of their 465-square-metre lawn. As the Globe described it, they used ‘any off time they [could] spare from upholding the law and keeping firefighting equipment in tip-top condition’ to grow tomatoes, radishes, Scotch kale, carrots, cabbages and more.” Much like today, there was a sudden run on seeds, and as a reporter tried to interview a seed seller about the boom, their answer was “We’re so busy selling seeds for Victory Gardens that we have no time to even discuss them.”

The results were staggering: in 1943, 52 million kg of vegetables were grown in Canadian cities, in more than 200,000 wartime gardens, yielding an average of 225 kg each. Our neighbours to the south managed to produce almost 40% of their own vegetables from 2 million gardens. Of course it wasn’t all sunshine and literal roses: Victory Gardens weren’t available to everyone, notably people of Japanese descent, including farmers, who had their land sold off after the government imprisoned them in internment camps after the war. (Thus, the new, Corona-inspired Victory Garden movement is using the name Cooperative Gardens.)

The interesting thing about all of this is I’d been planning a newsletter this very week about gardening because — SURPRISE! — growing your own food is also important to resilience in that other war, the fight against climate change.

First, let’s talk about food waste, which we know is one of the Big Bads of the climate crisis. According to a report by Second Harvest and Value Chain International, over 75% of Canada’s food waste happens before it even gets into your hands (24% in production, 34% in processing, 13% in manufacturing, 2% in distribution, and 4% in retail). If you’re growing your own food, all of those steps disappear, and much less will end up going to landfill. Shepherding vegetables from embryonic seeds to baskets of produce also gives you an immense respect for the whole process. I didn’t learn home canning until I was a gardener: because once you’re faced wth an abundance of beautiful, painstakingly grown food, you’re sure not going to let it go to waste.

Private gardens can also be more productive than large agricultural cropping. Studies from the Royal Horticultural Society and Which? found a competent allotment gardener can grow between 31 and 40 tonnes of veg per hectare. Compare that to a commercial farmer can get between 3.5 and 8 tonnes of wheat or canola, using about 20 different pesticides. (Of course, the private gardener is putting in more work per hectare too, but probably happy to do so.)

Growing your own produce also reduces the transport footprint of the food you eat. And while this is an admittedly small part of a food’s carbon footprint (less than 10%), I’m not turning away from any low-hanging fruit (literal or metaphorical).

Lastly, growing local food is especially important in areas where people don’t have access to fresh produce and suffer worse health and early death. Even when produce is available, there’s a big difference between a Whole Foods and a budget supermarket in a low-income neighbourhood, where, food activist Karen Washington told the Guardian, the produce “looked like it was secondhand.” These areas are commonly called “food deserts,” with but Washington urges us to use a more accurate name that reveals its systemic roots: food apartheid. These spaces are manifestations of racism and all its economic implications, and they all can’t be fixed by a cute little community garden. Nevertheless, the presence of a garden with free food does bigger, more important work than reducing carbon: it means community resilience, better health and more chances at economic security.

So grow for justice, grow for food security, grow to help the planet, but also, grow for the joy. Gardening has been the greatest surprise of my adult life, and the mental health benefits are even sweeter than a tomato still warm from the sun. Apparently, one of the key elements to sustained happiness is apparently the ability to keep learning, and gardening is perfect for that: I’ve been at this over the decade and am in many ways still a novice. Gardening also cultivates mindfulness and patience, not to mention it gets you away from your screen. Even now, in these challenging times, I put myself out for recess each day to potter in the garden. There’s not a ton that can be done, since it’s important not to “clean up” for at least a couple weeks longer, until temperatures are consistently over 10 degrees, so that all the beneficial insects have time to emerge. But even still, I’m finding things to do: turn the compost, relocate some raspberry canes, prune back the invasive Manitoba maple, check on my winter sowing. These recesses are my reset, and they allow me to come back to my work or the day in a much better mood. It’s no wonder that during WWI the Ontario Department of Agriculture promoted gardening as good for those “who suffer from tired minds and overworked nerves.” (*raises hand*)

Are you ready to dig in? Good! Here’s how:

Plant all the food.

You don’t have to dig up your lawn (though I fully support that, and Transition Toronto’s Food Up Front team will even give you free seeds), but grow as much as you can in the space you have. Maybe that means growing in some planters on a balcony (and it might help to expand your definition of “planter” to “anything that can hold a few inches of soil and plants”), or swapping out some of your traditional ornamentals for pretty edibles, like gorgeous purple kale, or sowing some herbs in a community planter. Grow as many plants as possible, and make as many edible as possible. There’s no such thing as too much produce, especially now, and you’ll always find someone thrilled to accept your bounty, whether it’s a neighbour or your local food bank. And if you have no land access, you could always take your cue from L.A. garden hero Ron Finley and do some guerilla gardening.

Make your yard fruitful.

Planting fruit trees is a long game, but it’s a great environmental choice. Not only do you get some hyper-local fruit, your tree will continue to remove CO2 from the atmosphere after you’re gone. Though many garden centres are closed due to COVID-19, you could buy affordable fruit trees, bushes, and other perennial edibles from the Tree Mobile, a non-profit project of Transition Toronto. They even deliver in the GTA! Personally I find that Raspberry Heritage bundle very tempting.

Share what you have.

Land. If you have a garden you’re not using (or that could support others), offer it up in a community group. The Stop Community Food Centre in Toronto used to run a YIMBY (Yes in My Backyard) program that matched people who wanted to garden with people who had one. My pal SJ got to garden in someone else’s yard after she put notes in neighbours’ mailboxes, and there are a couple of local florists who use other people’s yards to grow their beautiful blooms. Sometimes you just need to ask!

Seeds. I think one of the coolest things about plants is that you start with one tiny seed, and you can end up hundreds more by the end of the season. It’s mathematics of plenty. If you save seeds, now is an especially important time to share them, with seeds in such demand that racks are already reported empty in some spots. I fold little origami envelopes out of old magazines — a very satisfying TV-watching activity. (One caveat: a lot of groups have suspended trading or sharing any objects, so take care and be safe.)

Plants. This year I started extra tomato seedlings, since that’s something that can’t be sown outside here in Canada, and not everyone is willing or able to turn their closet into a grow-op like I do. But I’ll also dig up some garlic chives, yarrow, day lilies, goldenrod, oregano, and more, to share with whomever wants it. Post about free plants, and people will be at your door in a jiffy.

Construction skills. If you’re handy with a hammer, maybe you can (safely) help people build raised beds, support structures, or cold frames.

Knowledge. Though I’m far from a master gardener (a real certification you can get! #retirementgoals), I’ve realized I have a lot of know-how, and so I’m making awkward videos and more IG posts, and it may be because everyone is desperate for entertainment, but people find them useful! If you’ve been growing for a while, look for ways to offer information or mentorship, especially as a huge wave of first-time gardeners is getting started.

Learn more to level up.

I’ve learned so much from Gayla Trail, who is not only an incredible urban gardener, but a fellow Torontonian. I learned to garden with her book Grow Great Grub: Organic Food from Small Spaces, but her website is an incredible resource.

Join your local gardening group on FB, which is a great place to learn when and what to plant, and to get useful tips. Toronto also has a new group specifically devoted to growing and sharing food called Grow Food Toronto.

Looking for seeds? You can still buy from local seed growers (and the transit times make seeds safe to touch). I highly recommend Urban Harvest, Edgebrook Farms (great for cut flowers!), and Gayla Trail’s seed shop.

Wins of the Week

“We have an enormous opportunity to take the neighbourhoods we have and turn them into the villages we’re going to need to navigate through the future.” — Lisa Fernandes, permaculture instructor, in the Inhabit documentary (an inspiring watch for these challenging times)

Here’s some good stuff that’s going down:

As soon as it’s safe to exchange items again, I’m giving away four Cooperative Gardening Kits, with some plant divisions, a bunch of seeds, and the book that taught me how to garden, Gayla Trail’s Grow Great Grub, which I highly recommend to anyone. I’ve also made twenty smaller packs of pollinator-friendly seeds to give away. I’ll be offering them on various FB groups, and I have a feeling all will find a good home!

Stuart and his fam have switched to making their own ketchup to avoid plastic bottles.

Carey made hankies out of old receiving blankets (sooo soft!)

My wins supply is running low, so please send some good news my way! Are you growing food for the first time this year? Or stepping up your game? Tell me about it!

If this post is useful, please do like, share, and all the rest to help support the everyday eco-revolution.

xo JK

Yes! We've got to get ourselves back to the garden ...