Let’s start here: I love travelling. In my twenties and thirties, I’ve jetted all over this blue marble. I’ve petted (then-unsinged) koala bears in Australia, eaten noodles at a night market in Thailand, swam in Costa Rican waterfalls, tromped the cobblestone streets of Europe many a time. I don’t list these trips to brag but rather to tell you I get it — I think travelling makes us alive to the world in a way almost nothing else can. Travel is my greatest luxury. Also: this is my glass house. No stones will be airborne in this newsletter.

Flygskam, as eco polyglots may know, is the Swedish word for flight shaming, and while we’re not about shaming and blaming individuals here (corporations and governments — absolutely), let’s talk about why this phenomenon got its own word and how we might grapple with air travel in a warming world.

Since 1990, our flight miles have climbed 300%, thanks in part to dropping airline fares. And while flying only counts for 2% of global emissions, it does have the highest carbon price tag of any action in our regular lives. For example, flying from London to New York and back creates 986 kg of CO2 per flyer: that’s 1/12 of the average Canadian’s footprint for a whole year, or more than the average generated by a person in 56 countries. Think about that: one trip vs. someone’s whole life for a year. Or here’s an image for you: that same flight generates enough CO2 to melt 30 square feet of Arctic sea ice.

It’s not just jet fuel doing the damage, either. Negative flight impacts are effectively doubled (compared to the basic CO2 they release) by being high in the atmosphere, triggering chemical reactions that ramp up warming, and by contrails, those tails of exhaust that trap even more heat as they linger above us. (Interestingly, this effect is worst at night — during daytime flying, contrails can reflect some sunlight away from Earth.)

The flight paths of 162,637 flights recorded on one day in May 2019 (flightradar.com, via the Guardian)

But the realities of the modern world are that many of us have far-flung family, business responsibilities abroad, and dreams of seeing other places (or at least occasionally escaping the interminable February cold). How do we balance that with a world on fire?

See how your flying stacks up.

I think calculating your carbon footprint is a great exercise, regardless, and the fantastic Project Neutral makes it a breeze, but when I did one for my household, our air travel impact made my stomach drop. Here’s what it looked like:

Our flights were 5.96 tonnes out of our 10.8 tonnes. Over half. And while that was a busy travel year, it’s only four trips, three of which my partner went on — I’m hardly George Clooney in Up in the Air. We live in a small apartment and don’t own a car, but look how a few flights dwarf those pretty serious eco choices. Don’t get me wrong, I think all actions matter, and we need all the good ones we can get, no matter how small. But even if you’re keeping that thermostat at dad-sanctioned levels all year round, a few hours on a plane could spend far more carbon than you’ve saved.

Fly less.

I know, I’m sorry. It bums me out too. There are so many animals of the world I have yet to see and/or pet! So many swims to take in foreign waters! But this is simply one of the most effective things we can do on an individual level to fight climate change. I don’t expect anyone to give up air travel completely (and I won’t, either), but consider picking a destination closer to home for some of your trips — somewhere you can get to by car, bus, or train. (Plus then you can tågskryt, or “train brag”). The last couple of years my friend M and I have done weekend retreats at nearby off-grid cabins for that getaway feeling minus the commute.

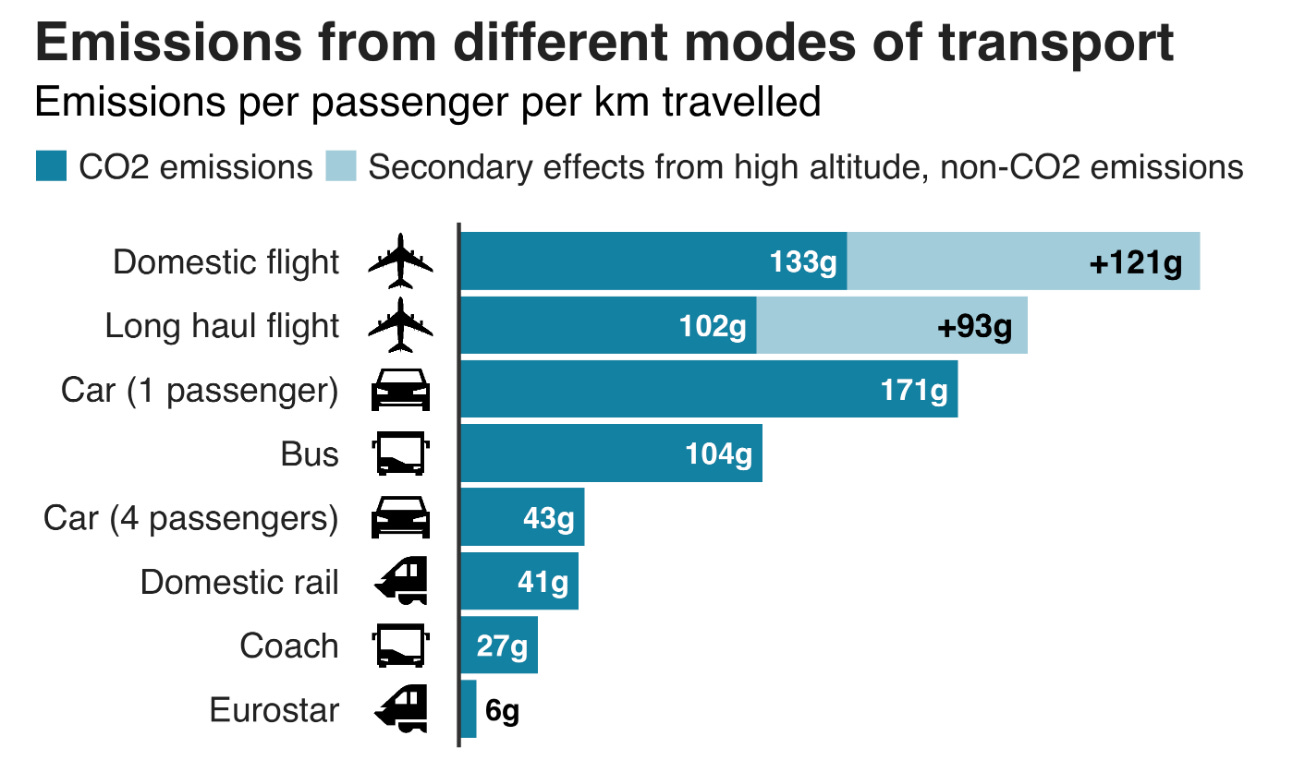

Comparing emission per km for different modes of transit, from the BBC

As for work travel, sometimes, like at a trade show or convention, your presence is necessary. But what about for meetings? I know that FaceTime is not as good as actual face time, but technology will improve, and we’ll likely get more used to it. The more people do this, the more normal it becomes. Plus, you’ll get a bunch of time back and avoid things like jetlag, security lines, and the person in front of you cranking their seat alllll the way back.

Also consider when you can bundle a work trip with a pleasure trip. This year I’m flying to San Antonio for work, which was a good opportunity to have our annual girls’ trip nearby. (And yes, it would be better to have it somewhere with no flying, but I am a mere mortal, committed to less flying, but not none, because if I’m honest, I’m not strong enough to scroll through all those vacation photos and remain grounded in all senses of the word.)

Fly better.

Planes burn the most fuel during takeoff, and shorter flights have a higher carbon footprint per mile travelled than long ones. So when possible, save time and carbon by selecting a direct flight.

You can also try to choose a more efficient airline by consulting this report from German non-profit atmosfair or this report and quickie chart on Canada-U.S. flights from the International Council on Clean Transportation. Newer planes (A320neo or Boeing 787 Dreamliner) also use less fuel, and generally medium-sized jets are the most efficient. If you’re a flight wonk and want to look at the international picture and dive deeper into plane efficiency, this report’s for you.

Lastly, remember that the more space you take up on the plane, the higher your impact. The carbon footprint of flying first class is two to four times that of flying economy.

Now I understand most people aren’t going to pick their flight based on fuel efficiency, and that price and convenience may carry the day. But if you save some money on that flight, maybe . . .

Throw some $$ at the problem.

Offsetting is contentious, and for good reason. At its worst, its a swindle (see: the Vatican paying for thousands of trees that never were planted) or a license to pollute, and at best an inexact (and often overly optimistic) science that only pays dividends down the line. (For example, planting trees has many benefits, but they’re not going to suck up significant carbon for at least a decade, will re-release their carbon when they eventually die, and it’s also possible they could get cut down, burned in a forest fire, etc.) Ultimately there’s no absolute guarantee you’ll offset the carbon you produce. But you know what definitely won’t? Doing nothing.

Offsetting may seem like the modern version of that classic Catholic hustle, the sale of indulgences, but I see it more as a luxury tax — because when it comes to flying, some of us are spending like carbon millionaires. Offsetting your flight can cost less than selecting your seat in advance or checking a bag and seems like a reasonable price to pay for a trip I’m going to take anyway. (And I’m too cheap to select a seat OR check a bag, so I must think this is important.) Offsetting adds something positive, even if it doesn’t totally undo the damage. Worst case, I’m out the price of a regrettable airport sandwich.

If you’re willing to jump onboard the electric-powered offset train, first calculate how much carbon your trip will create using a flight calculator. You could purchase your offsets through your airline — Air Canada works with Less, a subsidiary of Bullfrog Power. You can also buy them directly from an organization like non-profit Gold Standard, which is supposedly the highest standard in the world and endorsed by the WWF, Greenpeace, and others (and where Less gets many of their credits). Their projects come with governance, high-impact interventions, and measurable effects. It’s also fun because you can shop for projects that have human benefits, like improving water access or providing clean cookstoves. They’ve also created a gender-responsive project, which I find particularly exciting. If you’re still worried about the usefulness of your contribution, follow the advice of the Pembina Institute and the David Suzuki Foundation and choose a project funding renewable energy or increased energy efficiency (low energy stoves and appliances, industrial efficiencies). With Gold Standard, offsetting 1 tonne of carbon starts at US$10.

If that’s still too rich for you, Founders Pledge (a UK non-profit that encourages entrepreneurs to pledge 2% of their personal profits to charity and supplies them with evidence-based analysis) published a report that suggests donations to the Clean Air Task Force or the Coalition for Rainforest Nations can offset your carbon for around US$1/tonne. (You can also make your donations to both of these orgs tax-deductible in Canada by donating through RC Forward.) Make sure these donations aren’t ones you’d be making already — an offset should always be above and beyond.

If you’re flying for work, ask your employer if they’ll consider offsetting flights. In the grand scheme of travelling, it’s a small cost, but it will add to their eco cred.

If we want offsetting to be more effective, though, we need to stop relying on individual consciences and legislate that luxury tax. Some of this is already underway: Thanks to a 2016 UN agreement, the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), in the next decade any emissions that go beyond 2019 and 2020 levels will be offset by airlines. But for the next few years participation is voluntary, and sadly 2020 levels are already very high.

Another idea floated by the UK’s Committee on Climate Change is to institute a straight-up tax on the most frequent flyers: in the UK, 15% of the country is generating 70% of flight emissions. (Numbers are similar in the U.S.) The committee suggests a tax that climbs with miles flown, with funds being channelled into climate change initiatives.

Can technology fix this?

Jets are burning 80% less fuel than in the 1960s; emissions have gone up because so many more people are flying. This shows, though, that fuel efficiency can improve dramatically — especially when fuel is an airline’s largest cost and there’s great incentive to keep that cost down. Making planes from lighter materials, more streamlined design, electric power (in December 2019, B.C.’s Harbour Air conducted the world’s first electric seaplane flight), and improving airport efficiency (so that planes don’t have to circle, waiting to land) could all make flying less carbon intensive. According to a CBC interview, David Zigg, professor and director of the Centre for Research in Sustainable Aviation at the University of Toronto, thinks that significant carbon reductions are possible: in the future, flying might have 1/8th of the impact per passenger, per kilometre. A new study out of Imperial College London suggests that changing flying altitude could mean avoiding contrails — potentially lowering emissions by as much as 59%. Project Drawdown estimates that more efficient airplanes could remove 5.05 gigatons from the atmosphere by 2050 — and do it at significant cost savings. If planes do get more efficient, the key will be ensuring we don’t fall prey to the rebound effect, where potential savings are cancelled out by people flying more.

Flying less, sadly, isn’t a quick fix — we need to make it a lifestyle. That said, remember the frequent flyers bear the heaviest climate burden, and cutting their time spent at 30,000 feet is where the real gains lie. If you’re not in that category, choose your trips carefully, and when you take them savour them for the incredible luxury they are.

TL;DR

Calculate your footprint to get a sense of the impact of your travel.

Fly less. (I’m sorry. Don’t hate me.)

Take direct flights whenever possible.

Offsets are contentious, but I think are better than doing nothing: choose a reputable offset agency like Gold Standard.

Planes are getting more efficient (but we still need to use them less).

Learn more to level up

Read

For those of you who really want to do a deep dive into offsets, how they work, and how they are evaluated, I’d recommend this paper from non-profit think tank the Pembina Institute. It also contains an evaluation of many offset providers, so if you’re thinking of one I didn’t mention, check it out there first.

Listen

Three climate scientists, including the wonderful Katharine Hayhoe, discuss flygskam on The Current.

Now tell me . . .

How do you feel about flying? Do you offset, and how? Am I the ultimate buzzkill?