Environmental racism and environmental justice

Content warning: This week’s newsletter features discussions of anti-Black racism and police violence.

It’s a heavy time — especially so for Black folks. There’s the everyday mental and economic stress of month three of pandemic isolation, then add the brutal murder of George Floyd by police, which followed on the heels of so many other recent violent Black deaths such as Breonna Taylor (shot by police infiltrating the wrong apartment) and Ahmaud Arbery (shot while jogging by two white men). In the Toronto area, we have our own tragedies in Regis Korchinski-Paquet (who died in a 24-storey fall after police entered her apartment) and D’Andre Campbell (who was shot by police in his home after he called them for help). We have Amy Cooper, who weaponized her whiteness against Black birdwatcher Christian Cooper. Then is the fact that the pandemic disproportionately affect Black Americans, who are three times as likely to die of COVID-19 than white Americans. Race is a part of everything — environmentalism too.

I’m coming at this as a white person who is still unlearning and navigating a lot of white supremacy, and this week’s offering is intended particularly for those who are not subject to racism and, more specifically, anti-Black racism, in its many forms. If you’re serious about this work, let this newsletter lead you to keep learning from some of the voices I’ll include today.

I’ve mentioned environmental racism before, and now seems an essential time to go deeper. The term, coined by Dr. Benjamin Chavis, means that Black, Indigenous, and other racialized people often are forced bear the brunt of environmental degradation in their communities and are least able to leave them. The environmental justice movement was born in Warren County, NC, when the state decided 6,000 truckloads of PCB-contaminated soil should be dumped in a predominately Black community. The community fought back. The material was still dumped, but it brought public attention to the intersection of race and environment.

You can see environmental racism at work in boil-water advisories on First Nations, neighbourhoods next to pollution-spewing industry or a dump, contaminated soil where a person can’t grow food. It has very real health consequences, like cancer or asthma. It’s the mercury dumped upstream from Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation (Grassy Narrows) for 50 years. It’s communities so contaminated by industrial activity they’re known as “Cancer Alley” (Louisiana) or “Chemical Valley” (Sarnia, ON). It’s the one million Black Americans who live so close to a natural gas plant that they face a cancer risk above the EPA standards, and who, in general, breathe 38% more polluted air than white Americans. It’s seasonal workers exposed to hazardous chemicals as they harvest food. It’s shipping our “recycling” to China, Malaysia, Thailand for workers to pick through before the refuse is burned, releasing toxic smoke. It’s permafrost melting two to three times faster in the North. It’s brutally unfair, and it’s pervasive.

It’s easy, as an environmentalist, to think that the work you do, you do for everyone, because Earth is our common home. But Earth has some safer, healthier real estate, no? Those who are marginalized face a greater threat from everyday pollution and climate change, have different resources and different needs. For example, if you’re passionate about reducing single-use packaging, great! But a Black woman who lives under food apartheid, who is already dealing daily with the systemic injustices of racism, is not going to be able to access fresh food and package-free goods in the same way I can walk to a three stores in under five minutes and pay a premium for less waste. Reducing packaging might actually mean making fresh food more available, facilitating urban gardening, fighting for fair wages, supporting subsidized childcare, etc. Advocating for the environment means advocating for people, and for interdependent support networks that will benefit both.

Environmental racism happens within a country, but can also happen on an international scale: consider how much pollution we export when we buy stuff made in coal-powered factories in China (we track pollution by production, but consumption matters more), how our reliance on palm oil and other commodity crops displaces Indigenous people as it destroys rainforest, the water pollution that comes from growing and processing cotton in India, the pollution caused by worldwide mining operations (many of which are headquartered in Canada), and so on.

Most of the wealthiest countries have high populations of white people who have benefitted from centuries of colonialism, whereas the poorer countries are populated by predominantly non-white people that have been and continue to be exploited. They have paid the price for economic gain with their health, with their lives. As the effects of the climate crisis intensify, the people least responsible for our environmental woes are the ones most likely to die or be dislocated, and they’re already suffering decreased economic output. In a warming world, millions will die. Cyclone Amphan was just a preview.

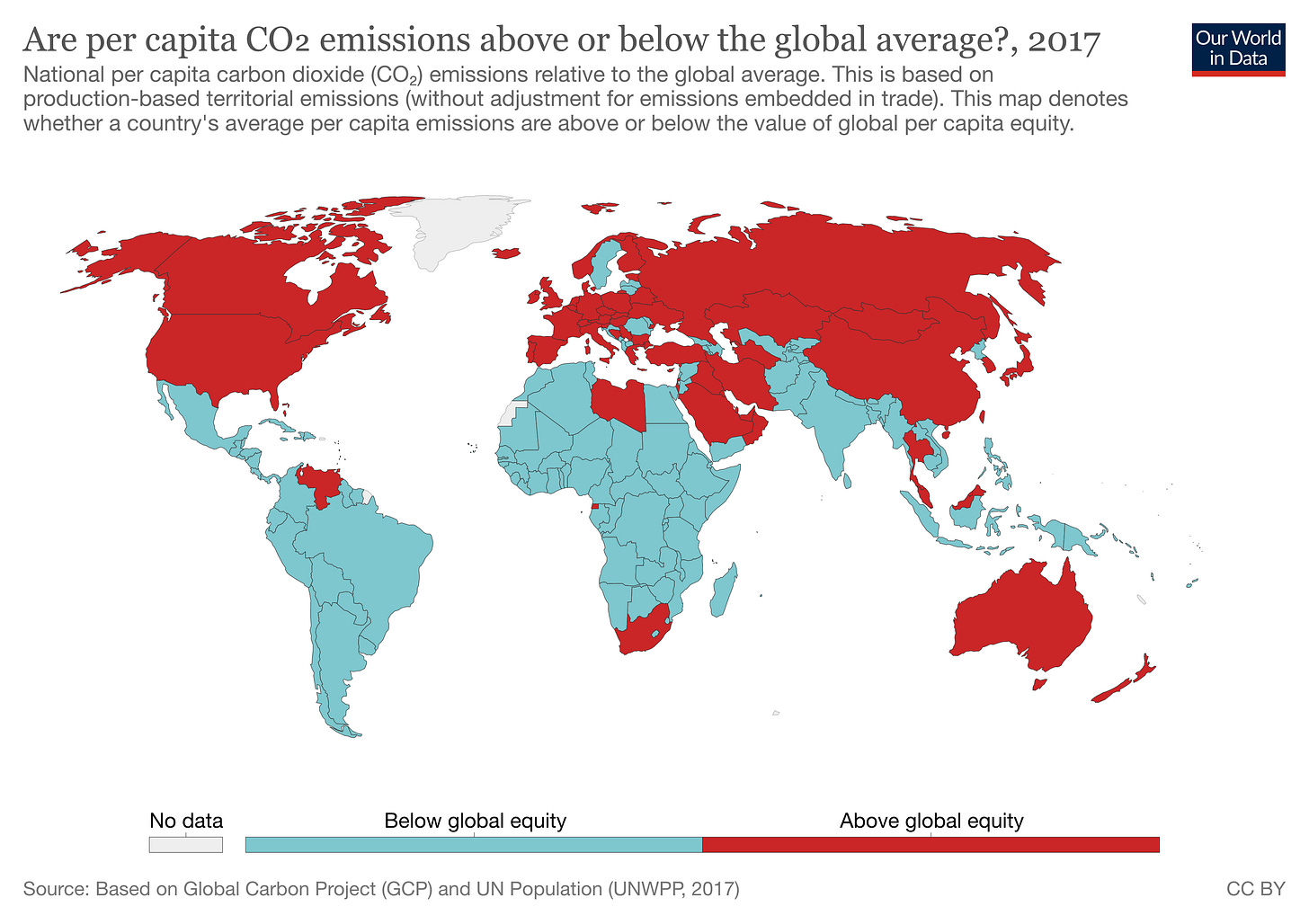

Let’s look at this map out of Oxford’s World in Data (here’s the interactive version), to see who is emitting more than their fair share of emissions (the red countries) and who is emitting less (the blue countries):

Guess who is suffering the most under the climate crisis? The blue ones.

And if you’re looking for a handy statistic, here it is: the world’s richest 10% produce half of the world’s carbon emissions. The poorest 50% (aka 3.5 billion people) produce only 10% of the world’s emissions.

You can get a sense of this going over the interactive map: compare our per capita emissions in Canada (15.64 tonnes/person) to Mali (0.09 tonnes/person) or Pakistan (1.01) or Myanmar (0.47).

So what can we do about environmental racism at home and abroad, and in the environmental movement itself? (Check out this edition of Emily Aitken’s excellent Heated newsletter for more about racism within the movement.) It’s a many-headed hydra of a problem, and sadly not one that’s going to give us many quick wins. Anti-racism and environmental justice are lifelong work. Before we get into the specifics, here’s a great intersectional environmentalist pledge with general principles from @greengirlleah:

Now how can we start doing the work and putting these principles in to action?

Listen to and amplify activists who are Black, Indigenous, or people of colour (BIPOC).

If I’m honest, for a long time I saw Instagram as a refuge, a place to look at pretty flowers and cute animals. It was a welcome break from everyday life. But refuge is itself a privilege, and it’s more important that people have it in real life. I’m still working with my bias towards sharing content that is “pretty.” (It’s stupid, I know.) But I have a responsibility to engage, and I’m grateful to those who educate, who speak truth, who prompt and provoke. Some eco-oriented and justice-seeking people I’m learning from on IG: @ajabarber, @plasticfreeto, @climatejusticeTO, @sundanceharvest, @queerbrownvegan, @seedingsovereignty, @mikaelaloach, @greengirlleah, @ayanaeliza. Once you follow, engage with those posts; save them for later if there’s a lot to process. Take the time to listen and learn. Don’t put the burden on people of colour to personally educate you: even if you have good intentions, stay out of those DMs and comments, bud. The World Wide Web is here for all of your questions. If you need to talk it out with someone, talk to a white friend (like me — always willing).

Educate & execute.

Continue that education beyond your Instagram page — vital if you have any hope at being a good partner in dismantling racial injustice. You can read excellent books both about racism itself (I’d recommend White Fragility and So You Want to Talk About Race? as great starting points) and environmental racism (try works like Growing Smarter by Robert Bullard, the father of environmental justice). You could watch Ellen Page’s documentary about environmental racism in Nova Scotia, There’s Something in the Water, on Netflix, or the inspiring community gardening doc Urban Roots (rent on Vimeo. And yes, I have a gardening doc for every occasion). You could listen to Hot Take, Mary Annaïse Helgar and Amy Westervelt’s intersectional, critical climate coverage. (They also have a newsletter.) You could attend a virtual launch for Who Killed Berta Caceres?, a new book about the Indigenous land defender. There’s also a plethora of different resources about race, including articles and podcasts compiled here. All of this work, whether explicitly environmental or not, helps you more actively anti-racist in your environmentalism.

Then don’t just learn, implement. Use what you’ve learned to fight injustice where you see it in your spaces, to amplify voices of BIPOC, to support others doing good work. Does this sound hard? It can be. But it’s vital.

Donate.

I know it’s a hard time to donate money, and it’s not an option for everyone. That’s okay! (Donating time, amplifying voices online, signing petitions, and writing and calling representatives are also a great options.) There are lots of great organizations that work to protect Black lives, like your local chapter of Black Lives Matter, the NAACP, the ACLU, or U.S. bail funds. But if you’re looking for a place to donate with an environmental bent, look for organizations with BIPOC folks in leadership positions, or that are entirely BIPOC-led. Look for ones that aren’t just doing charity (reinforcing existing hierarchies), but empowering people with education to help fight systemic injustice. Look for programming that specifically looks to uplift and benefit BIPOC, that has goals and an approach that are intersectional. You could support urban farming and food education at Black Creek Community Farm or Sundance Harvest, youth-led Climate Justice TO, or Indigenous-led Seeding Sovereignty, for example. I’m a frequent supporter of Foodshare, which isn’t strictly an environmental group, but meets the criteria I mentioned, and more sustainable food systems are a vital part of a greener future. If you have BIPOC-led eco groups you give to, please let me know!

Let’s never forget that protecting nature includes protecting people — otherwise the planet would be better off without all of us.

I know, this is all so much harder and nebulous and long-term than sorting your recycling properly. But this is the big work, the important work. We all deserve equal access to safety, to health, to an opportunity to prosper. To all my white readers, it’s time to work to make those things universal rights and not privileges.

TL;DR

Watch this three-minute video from Grist! (A good watch even if you read every word this week. You have an extra three minutes, right?)

Wins of the Week

“Revolution is not a one-time event.” — Audre Lorde

“Social justice cannot wait. It is not an optional ‘add-on’ to environmentalism.” — Leah Thomas (@greengirlleah)

Jenna and Kevin have taken up urban cycling! Kevin even got a bike trailer to haul big loads of groceries.

Jessica is focusing on sewing and alterations, so she can get through the year without buying new clothes. (And if anyone can master a new handicraft in no time, it’s Jess.)

Thanks to everyone who stayed with me through a tough topic this week. So much of this can feel ugly and uncomfortable, but let that be a sign of all the work we have to do.

xo

Jen

P.S. Big thanks and love to my weekly editor, Crissy Calhoun, and special guest editor Beth Lyons for helping me make this edition better! Feedback is always welcome.